The Basalt Vista is a new affordable housing project in Basalt, Colorado in the north of Aspen. It’s also a living laboratory to test advanced power grid technologies and systems. They are now testing a new method referred to as Virtual Power Plant (VPP) to distribute electricity across the neighborhood.

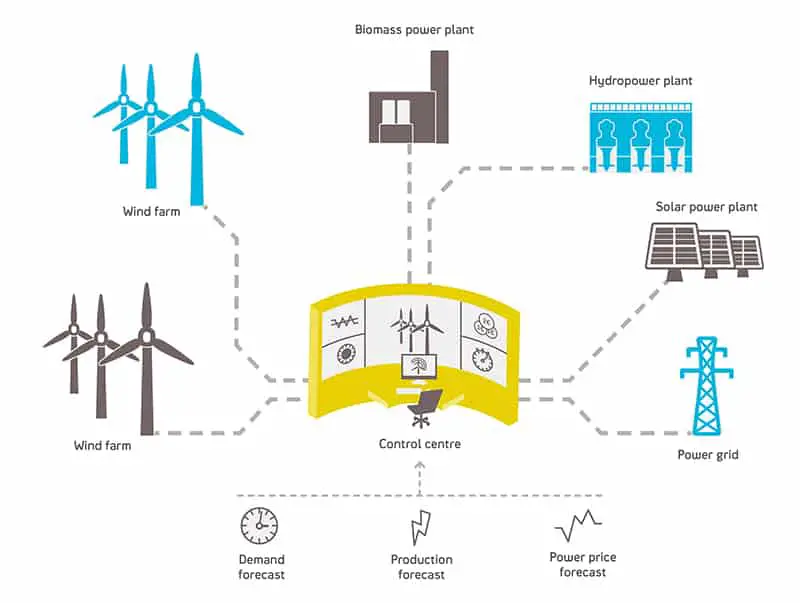

The residents of Basalt Vista are relying on an experimental, virtual power plant to distribute electricity to their homes rather than a centralized remote power plant. Similar to microgrids, virtual power plants consist of distributed energy resources (DERs) or systems such as rooftop solar PV panels, Electric Vehicle (EV) chargers, and battery packs.

The difference between virtual power plant and microgrid is that virtual power plants aren’t really designed to disconnect from the national grid (traditional grid) as is the case with microgrids that can disconnect from national grid and run autonomously. Instead, VPP aggregates and control distributed energy resources so they can achieve the functions of a large centralized power plant—generating and harvesting electricity for the wider grid.

Read more on: All You Need to Know About Microgrids – Concept Explained

In the neighborhood of Basalt Vista each house generates clean energy from the solar PV panels installed on their roofs and stores it for later use in battery packs which is a potential example of a more sustainable energy infrastructure.

Holy Cross Energy, a member-owned utility company in the area, helped add an internet-connected device to each Basalt Vita home that controls the flow of electric power within the local grid, as well as the larger grid linked to a regional power plant, if needed. These devices will help the control process as when one home produces more energy than it needs, it can independently make the decision to redistribute it to its neighbors or store it in battery packs for later.

“We don’t have to deal with any of the machinery,” resident Katela Moran Escobar told Wired. “The house works all by itself.”

Normally, an electric power plant will generate electricity and distribute it to the area. But because it does so in real-time, its operators need to predict how much (load) the area will need, often resulting in a wasted surplus energy. That means retrospective cost and, if the power plant burns fossil fuels then it’s a needless environmental destruction.

“Living in an affordable house with net zero energy use is great for the environment and our finances,” Escobar told Wired. “I hope this model is replicable in other places.”

So far, the results from various VPPs trials have been promising. VPPs help both utilities and customers by saving money, increasing the amount of renewable energy systems and strengthening the resiliency of local power networks.

![Types of Engineers and What they Do [Explained]](https://www.engineeringpassion.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/types-of-engineers-and-what-they-do-280x210.jpg)

Leave a Reply